Teaching kids to serve the collective undercuts ambition, achievement

- Joanne Jacobs

- Jul 26, 2025

- 2 min read

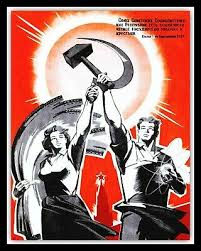

Indoctrination works, writes Sergio Martinez of the Foundation for Economic Freedom. Teaching Marxist ideas doesn't make children love socialism, but it shapes "their values, ambitions and sense of agency" for the worse.

In 1973, the fifth-grade social-studies curriculum in Pirkkala, Finland was rewritten to mirror Soviet textbooks. "Capitalism was depicted as oppression, the Soviet Union as a moral compass, and the free market as a source of inequality," Martinez writes.

Compared to students who received the standard curriculum, these students earned 10 percent less as adult, researchers found. They went as far in school but "made different career choices: public-sector jobs, artistic paths, and professions that aligned with values they had been taught early on — solidarity over self-interest, ideology over income."

After a year of Soviet-style lessons, many Finnish children had "more negative opinions" about socialism than before, reports YLE. (They were tested at the start and end of the year.)

One exam asked (correct answer in boldface):

“Why is there no unemployment in the Soviet Union?”

1. There are so few people living there

2. The government arranges work for the unemployed

3. Long-term planning of industry and business

4. Short working days

Pupils were also asked how socialism can be achieved:

1. Armed conflict in a civil war

2. A revolution carried out by the working class

3. Via parliamentary elections

4. By foreign powers’ intervention

Poland removed Soviet-style political indoctrination from school curricula in 1954, he writes. "This included removing content explicitly praising the importance of obedience to the Soviet regime and adherence to Marxist-Leninist values, along with Stalin-themed recitation competitions."

Researchers analyzed what happened to students just before and after the change. Decades later, those who "experienced one fewer year of Marxist-Leninist schooling were more likely to complete high school and college," and more likely to be employed, writes Martinez. "When you stop rewarding obedience and start rewarding merit, students begin to believe that their choices matter. Ambition wakes up."

Long before the rise of Nazism and Soviet Communism, schools have taught children "to see the state as a supreme moral authority," he writes, citing Ludwig von Mises in The Political Economy of International Reform and Reconstruction. A society of conformists will have a lower standard of living.

Americans value individualism more than Europeans, and one strain of progressive education is very much about letting every child pursue his or her own interests. First graders have their own pronouns! But teaching children about climate change and systemic racism can undermine students' sense of agency, argues Ian Rowe and others. If it's all hopeless, why try? I think we need less doom and gloom and more of the old can-do spirit.

Since no one wants to review how Finland outperforms the U.S., the applicability of any study of students in Finland to students in the U.S. is very limited.